Petra heard her mother call from far end of the beach. She circled back slowly and even now, while

retracing her steps, she kept an active eye on the stones in the sand ahead.

The bottom of her left pocket stretched well down against her skinny sun-browned

thigh. There were already too many rocks

in her pocket to walk comfortably. Each

step created a dull thud and clatter, moist and gritty, rattling with rocks, a

sound that mimicked the clink-clank stones made as they tumbled in the waves

further up the shore. Her right hand grabbed the stretching waistband of her

shorts. She had been hiding this

favorite denim pair since her mother had jokingly threatened to throw them out.

“You’ve all but destroyed them, and in just one summer,” her

mother quipped.

“You know you’ll need to pick out just a few rocks to bring

back home.”

That might prove to be a nearly impossible task.

Collecting them was a momentary obsession that she easily

slipped into, and for some long clock-less minutes it was all consuming. It was a simple-minded pastime and yet at the

same time decidedly mindful.

And what fault is there in filling ones hands and then

pockets with such earthly beauty?

She found happiness in such singular moments, and joy in the

solitary safety of walking and collecting.

And this summer her collecting had been given a new

dimension. One simple idea, an aesthetic

value was added to the process by two disparate members of her family.

Her younger cousin Timothy, down from the city with his

family, has shouted out for all the universe to know, and no one in particular

to hear,

“I’m looking the round ones, the rounder the better they

skip…”

When the water was flat, like on this morning, he could

indeed skip a round-flat stone six or eight times before it sank.

The rounder the better…

She humored him for a while by supplying him with flat round

stones.

“Bring me more ammo,” he would call out, in his war with the

waves.

He soon disappeared in the fog, distracted in the heat of

battle by a horseshoe crab patrolling the shallows.

And she, distracted in another direction by the quest to find

round stones. Round flat disks, spherical

not-quite-eggs, round in gray or brown, round and large or small.

Round, circular round.

The rounder the better.

Perfectly round.

At first it seemed a fool’s quest.

Yes, there were many nicely rounded, but somehow in the

mystery of wave and mineral, they had been shaped without a perfect

radius. The eye of a child could see the

beauty and the imperfection.

So the collection was always small, the best kept on the

windowsill above her bed.

One’s that were close.

Like in horseshoes, she thought. Points for being close.

And the stones that were judged less close were pocketed some

mornings and returned to the water.

Deselected.

They needed more work, she thought.

We will meet again, she confessed.

The second influence on her collecting was her Uncle

Newman. It was he who invited family and

friends to his old rambling beach house where they stayed each summer. It was a wooden three story farmhouse with

wrap-around porches. It had stood for a century and a half at the crest of a

small hill overlooking a long sweeping crescent beach. The sandy beach eventually trailed off to the

north turning into a rocky headland that featured a lighthouse which overlooked

a broad sweep of ocean.

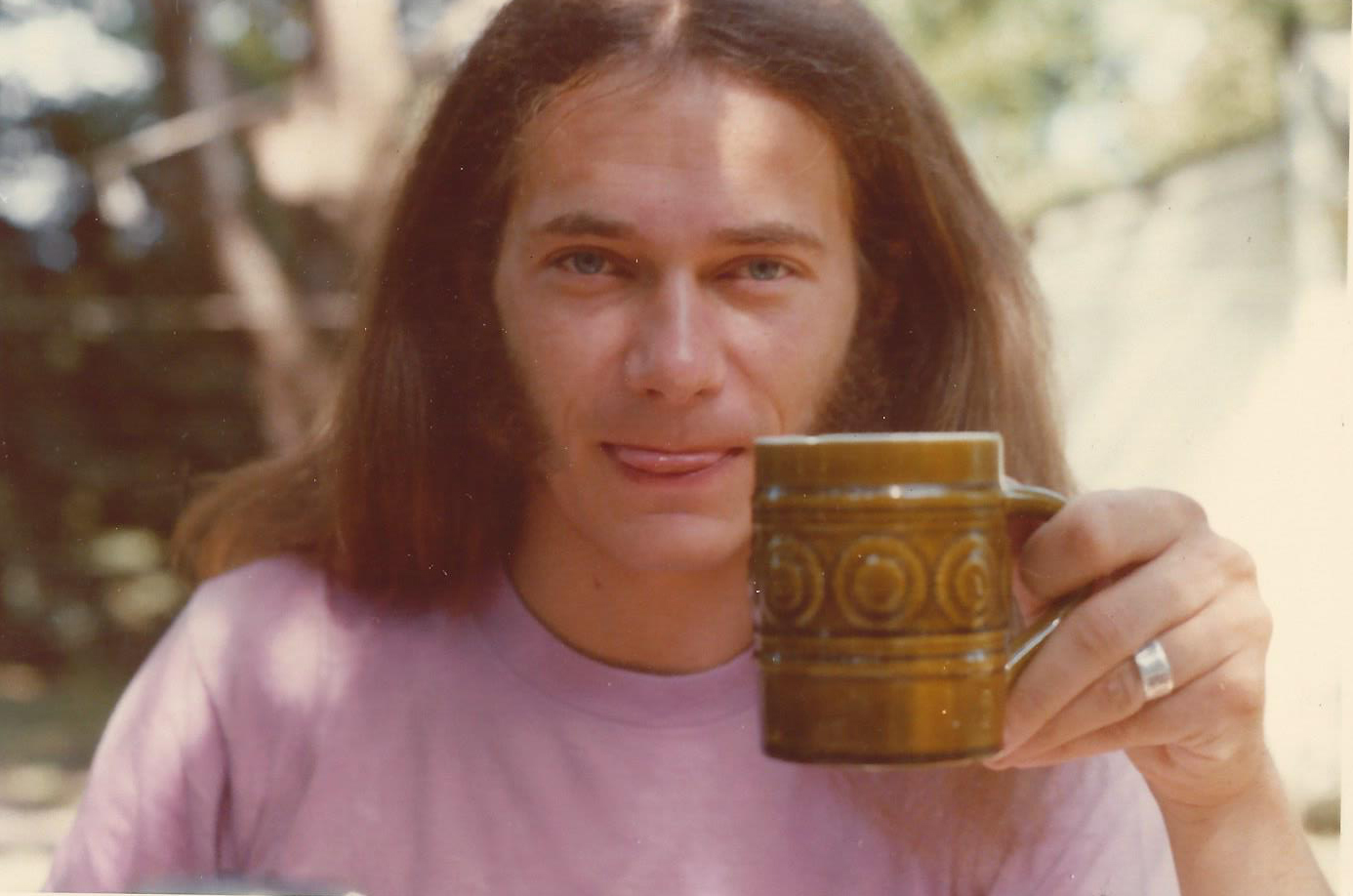

From Petra’s perspective, he was very old, maybe as old as

the house itself. She recalled a family

get-together the previous year celebrating his eightieth birthday. What a glow those candles made.

And although he was old, he still stood tall, only slightly

bent with age. His hair was white,

thinning but not gone. His eyes were

blue and clear. The skin on his hands and face was spotted and creased and he

smelled, not unpleasantly, like a baseball mitt. Perhaps it was the leather bound journal he

often carried, and could sometimes be found writing in it.

“I use it to keep track of my work,” he once explained, when

she asked about it.

He showed her a couple of pages; one with writing and a couple

with drawings of circles and symbols and numbers.

“I’ve been working on a project for many years…some think it

foolish, but…” he added as he slowly close the cover.

He reminded her of pictures of Santa Claus. Santa being the only other old man she was

familiar with. And indeed he was good

natured and pleasant, though not overly so.

He smiled at her with a Santa-like twinkle, and asked her occasionally

about her rock collecting.

She showed him a rounded stone she had collected and told him

that she was looking for a perfect one.

He laughed a kind laugh and explained that he would like to

see one himself, before…

He then opened his journal and sketched her stone. He took out a thin ruler and measured across

it in several place. Next he did some

arithmetic, it seemed.

“Pretty close,” he said to her, “but not perfect.”

“People have been trying to find or make something perfectly

round for a long time.”

“It interests me too, greatly.”

“I’d like to see a perfectly round stone someday...”

Days flew by as they can, if one is fortunate enough to spend

time at the seashore. Grey skies and

fog, hot sun, wind and wild waves push the hands of the clock and pages of the

calendar, until all that was left was a few precious hours, a few last moments,

one last swim, one final cool morning walk on the beach, the memories of which

would need to last until the next fortunate summer came around once again. There always seemed to be another summer.

Petra set out along the upper beach and walked to the south. As the sun labored in its attempt to burn off

the morning fog, she could just make out the stream that cut through the sand

as it rushed down from the marsh above the dunes. She would go that far and then need to head

back. She had promised her mother that

today she would cull her rock collection. Ughh. As a compromise, Uncle Newman had suggested

that she build a rock cairn on the beach across from his house. He said that it would surely mark the way for

her to return someday.

She worked her way down the beach until she reached the wood

and wire fence that sectioned off this portion from the rest. When she first encountered it back in early

June, she was offended. It was a barrier

that intentionally and arbitrarily broke her freedom. When she saw the sign explaining that it was

a protected area, set aside for Piping Plover nests, she relented. Later, she met Marguerite, a volunteer who

helped beach goers understand the plover’s needs and explained in a gentle,

firm manner why the beach was closed to human activity. She made people feel that by not walking in

the nesting grounds they were doing something important.

Petra had sat with Marguerite often under her broad umbrella

and talked about the birds and their natural history. She enjoyed using the binoculars to view the

almost invisible nests, the “scrapes” hidden in sand mixed in among the oval

egg-shaped stones. She thought that this

ingenuity certainly deserved a chance.

And the chicks in their first few weeks before they fledged were so

endearing. And while it broke her heart

to see an empty nest, victim of predation by raccoons, it also gave her joy to

see them trying out their newly feathered wings and taking their first hopping

attempts at flight. A few short weeks

later, all the nests were empty. And

now, Marguerite was gone and the nesting ground looked much like the rest of

the beach.

Petra pushed her way through the wire and wood snow fence

where it met the large rock rip-rap at the top of the beach. She walked cautiously into the nesting

grounds, but saw little evidence of birds.

No plovers swooping down in defense, no parent birds limping away down

the beach feigning injury. She had hoped

to see the scraped out nests or maybe a fragment of an egg shell, but a strong

storm with driving wind and rain earlier in the week had erased all traces of

the nests. Now the high beach looked

much like the rest of the upper shoreline; sand, rock, wrack and a few big logs

that had drifted ashore to rest after some unknown voyage from a distant

location.

It was on one of these logs that she settled her back. She had learned from Marguerite that if you

sat still, you saw things: everyday occurrences that most often go

unnoticed.

Almost immediately she saw the plovers. She feared that she

had violated their privacy and the sanctity of the nesting ground. As she sat

motionlessly she watched them run along the shoreline and then finally

disappear into a small blowout between the dunes. They were moving, not specifically focused on

the nesting ground, but working their way in a zigzag manner down the beach,

until at last they were lost in the mist.

And when they did not return, Petra assume to her relief that they were

just passing through; foraging and fattening up for the soon to come migration

south. She let out a deep sigh.

She stood and shook off the sand and her guilt.

Curious about the blowout in the dunes, she walked up and

explored it. As she passed through she

noticed that the wind had deposited several plastic bags. Almost instinctively she picked up the first

two she saw and stuffed them into the back pocket of her shorts. One more, wrapped around a blade of beach

grass caught her eye. As she tugged it

free, she noticed the stone, half buried in the sand. It was a beige-gray color, with specks of

black mica, and a band of white quartz. The stone had a pleasant heft as she lifted it

from the sand-drift, and almost immediately she noticed that it fit comfortably

in the palm of her hand. When she closed

her fingers around it, they wrapped it like a sheath. Casually she tossed it up and caught it in

her other hand. The surface was polished

smooth. It was nicely rounded and more

flat than egg shaped. It might make a

good skipping stone. But for now, it found a temporary home in her short’s

pocket.

As she walked up the driveway from the beach, the black car

parked there gave Petra a start. She did

not recognize it nor did she recognize the tall man with the black bag who was

now exiting the side door of the house.

He nodded to her solemnly as they passed on the walkway.

This is wrong she thought, as she swung the screen door.

Entering the kitchen her eyes almost immediately met with her

mother’s. They were reddened and

swollen.

“Your Uncle Newman has had a stroke Petra, he’s very

sick. The ambulance is on the way to

take him to the hospital.”

Petra’s eyes turned from her mother toward her Uncle’s room

just down the short hallway from the kitchen.

The door was ajar and she could see her father standing at the foot of

the bed.

And in a heartbeat, she was standing next to him.

“Daddy…”

“You can talk to him for a moment. He can hear you, but he seems to be

paralyzed, at least on his right side…”

Petra stepped to the bedside.

She was frightened to see his lifeless right arm and his mouth oddly

twisted open. Her fear subsided in the

next moments when he turned his head ever so slightly and blinked a soft

smile. Petra returned the smile

cautiously while struggling for something to say. Then, almost unconsciously, she reached into

her pocket and fingered the stone from the beach.

“I found a nice round stone today,” she said, gently placing

it on the covers pulled smoothly across his chest.

Then with some effort, he lifted his left arm and slowly,

gently, drew his thumb and forefinger across the diameter of the stone. He moaned a low resonant tone, almost a hum

and then closed his eyes. Petra though

he might have fallen asleep, or…

A long moment later, he opened them, and laboring more,

looked across the bedroom to his desk.

She followed his gaze and noticed his leather journal and saw a paper

folder once, placed next to it.

What did he want her to do?

Just then, her mother entered the room.

“The ambulance is here.”

“Petra, you need to…,” her mother called, gesturing for her

to come. She met her on the braided rug

half way across the room. She took her

mother’s cool hand as she looked back once more toward her Uncle. Together they walked out and sat on the

glider on the front porch. It creaked mournfully as it moved to and fro.

The sky had opened later that day and soaked the earth with a

gentle rain that continued into that evening.

After poking mindlessly at her diner, she climbed that back stairs. The well-worn tread-way moaned a familiar

sound but the wood beneath her feet seemed uneven, and she grabbed the handrail

to steady herself. The plinking of the

rain in the gutters above and its drumming on the porch roof below led her to

an exhausted sleep.

The heart and the mind have a way of blurring moments,

running them together so that the sharp edges of emotion do not jab too hard

into the softer places where care and love reside. We protect ourselves from the pain of loss by

seeing it more mercifully through this haze.

It is a form of self-preservation. In due time the haze clears. It clears when we are ready.

And so it was for Petra when her Uncle Newman died the

following day. She remembered people

weeping and even the sound of occasional laughter. She remembered hugs from family and seeing

many people who she did not know. She

remembered food and flowers, solemn and kind words, ceremony, and black clothes

and hearses. She remembered packing her

things, clothes and books and rocks. She

remembered echoed sounds, vague surroundings, and the taste of tears.

And then somehow she was suddenly back home and back in

school, as if the weeks had passed ignoring the clock and calendar. She found herself with friends and

classmates who chattered and laughed. They did not notice the fog of loss Petra

was in and she did not bother to explain.

Why would they want to know, and how could they understand?

Her mother had asked her on several occasions to unpack her

summer bag, which was still pushed under the side of her bed.

She did not want to open it.

And then on one early fall day, a sunlit Saturday morning

cool and calm, Petra wandered purposelessly into the back yard and climbed into

the tire swing hanging from a stout branch on a large oak. Sitting in the tire, she twisted the rope and

then picked up her feet and let the rope unwind. It spun her quickly around, slowed, then

rewound and unwound again. Listlessly

she wished that this would just go on forever, but at last the rope and tire

and Petra all came to a stop, facing the street in front of her house. Forcing her eyes to focus, noticed Mr.

Braughigan the postman walking up the sidewalk.

He was gesturing her way with a tan colored envelop.

“You’ve got some mail,” he called, as walked across the side

yard toward her.

“Here ya go…special delivery.” He handed her the envelop over

the side yard fence.

Petra slid her thumb under the sealed flap. Inside she found two papers. The first one was a note:

Dear Petra,

I was cleaning at the beach house and I found this note

addressed to you. I though you would

want it. It is from your Uncle Newman.

Much love, Aunt Sarah

The second one was also a note. It seemed to have been ripped from a

notebook…from a journal.

Dear

Petra,

I

don’t know if I will ever discover the right math need to create a perfect

circle. Perfection it seems, is a

difficult goal to achieve…

But

I recently learned from a good friend that looking for perfection is just as

important.

Thank

you for showing me the beach stones you collected. They are beauties ever one in their near

perfection.

Keep

looking and seeking and enjoying.

Love,

Uncle

Newman

Below at the bottom of the page was a drawing of a nearly

perfect beach stone. Rendered in ink,

it looked like the ones that she had collected and had shown him last summer.

She drew her thumb and forefinger gently over the stone drawn

on the page and after a moment, she slid the notes back into the envelop and

walked towards the house.

It was time to unpack

her bag, she decided. She needed to see

the rounded stones buried in the bottom.

She needed to put them

up on her windowsill.